The Museum is now open as the end of winter reckoning has taken place and whatever debts we thought we had have been paid to no-one. How tiresome the world is at present. Maybe we should all indulge in a private, personal version of Pharmakon. In silence. The Museum is here for you, as a place to escape, a digital milk bar, worshiping the healing power, and bounty, of paper.

Category: Accringtonia

Accrington Red Brick Coalbunker Interzone #2

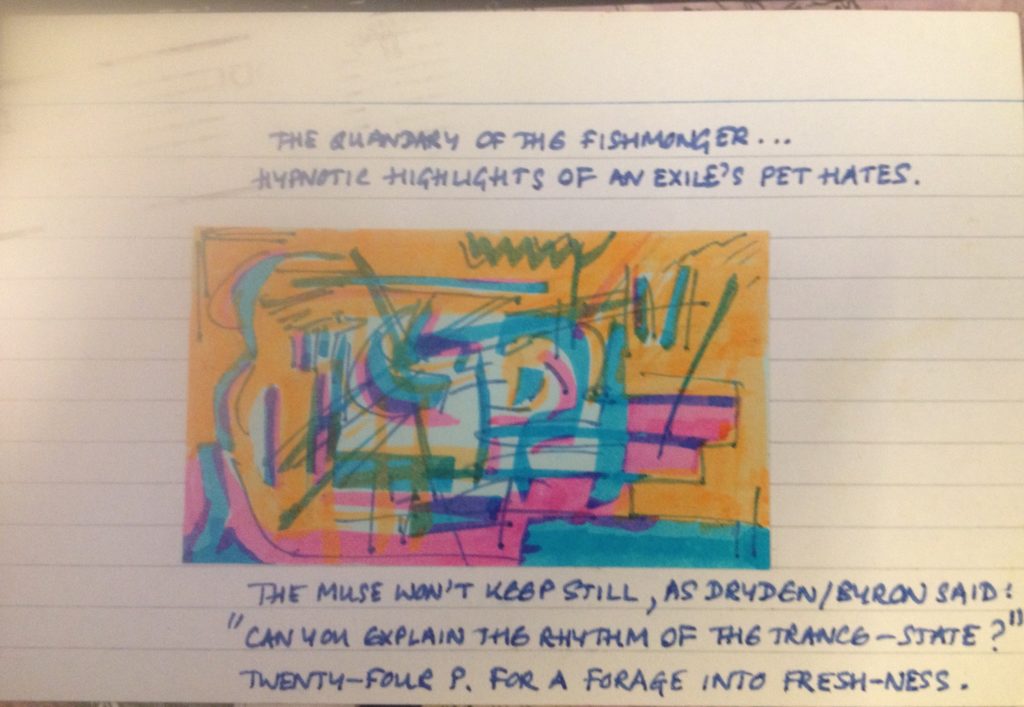

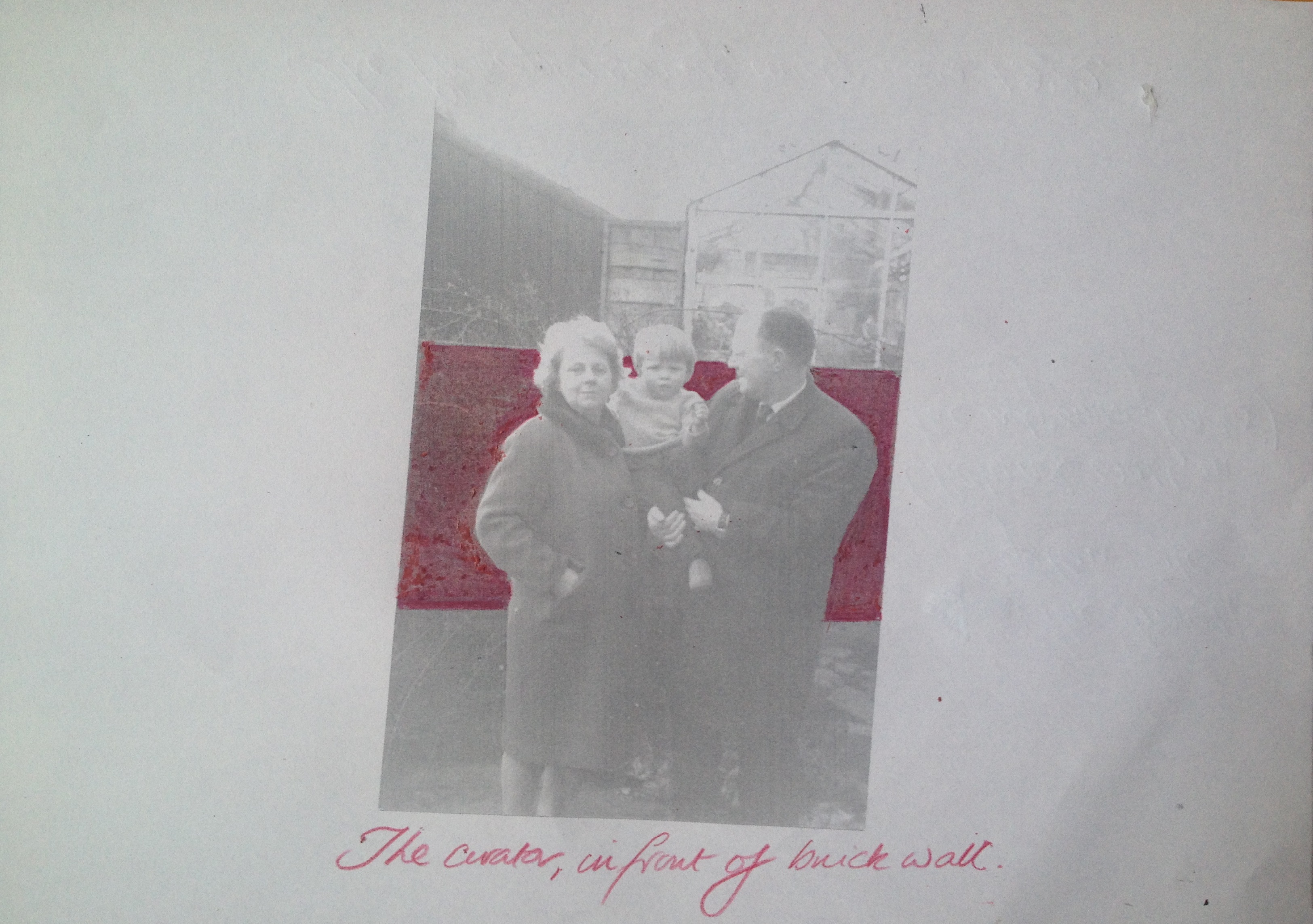

I have strong memories of mucking about in the grate of the new house we moved into in 1972. The grate – where water from the kitchen would collect – was a constant source of fascination. Staring at the ripples of water would induce a trance-like state. Airfix soldiers would drown, and my brightly coloured, too-light all-purpose play-ball would inevitably find its way there.

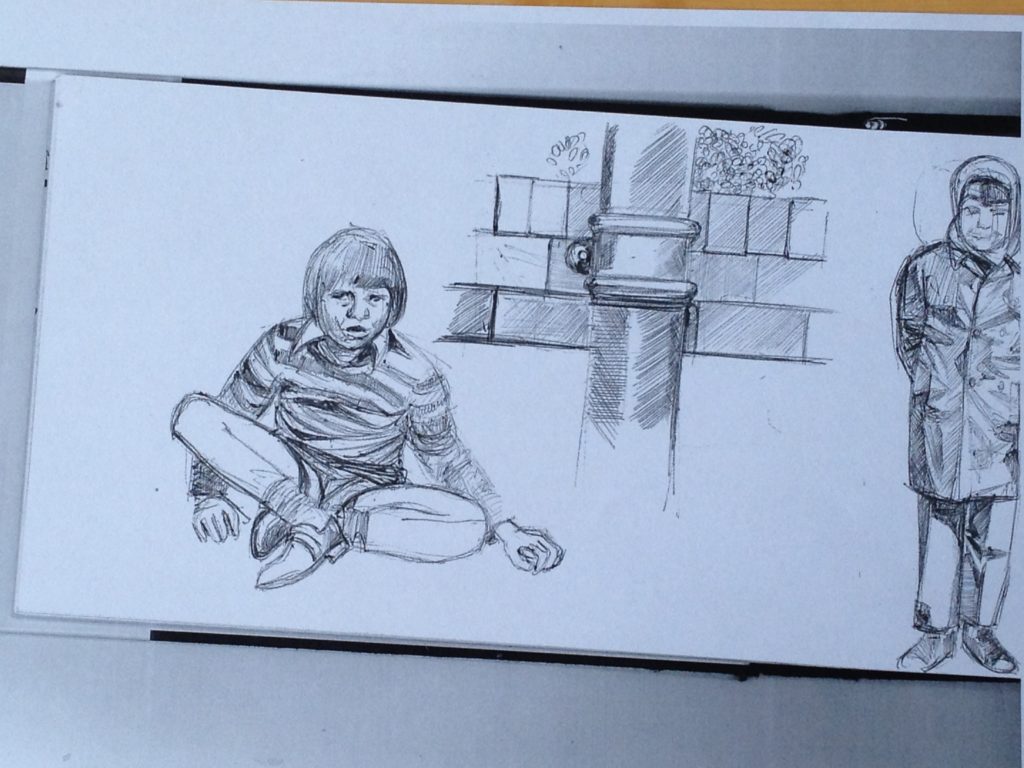

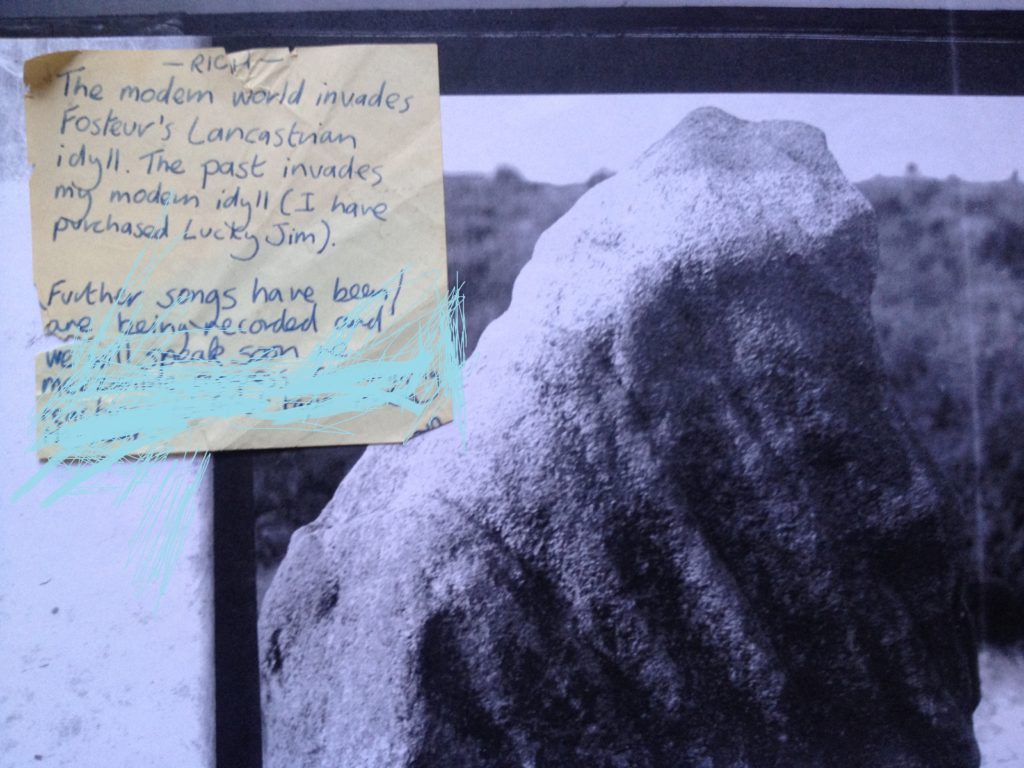

Recently, some kind of time-bubble opened up and I found myself repeatedly sketching the bricks of the kitchen wall by memory, or doodling from old photographs of myself in my favoured interzone, the patch between the coal bunker, the backdoor and the grate. How soothing Accrington’s red brick is, able to withstand the warm, benevolent Lancastrian gloaming, damp and accumulated industrial filth, able to stand out alongside the blackened, blasted sandstone.

Blue #5

There is a peculiar shade of blue that pervades certain parts of Accrington. Not always seen, it can nevertheless be sensed as a strong visual memory over long periods of time and sometimes in other places, far removed from this former manufacturing town in East Lancashire.

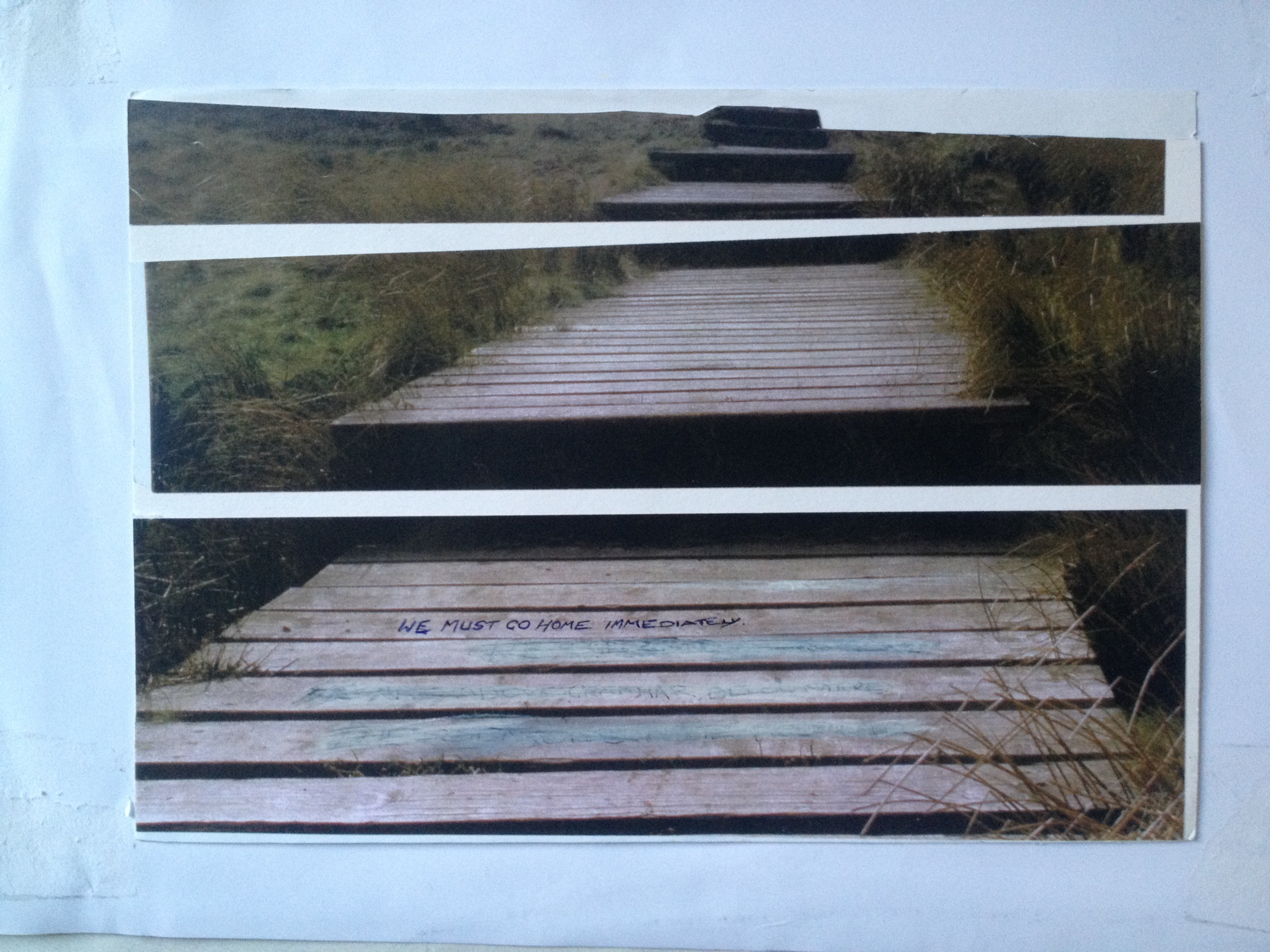

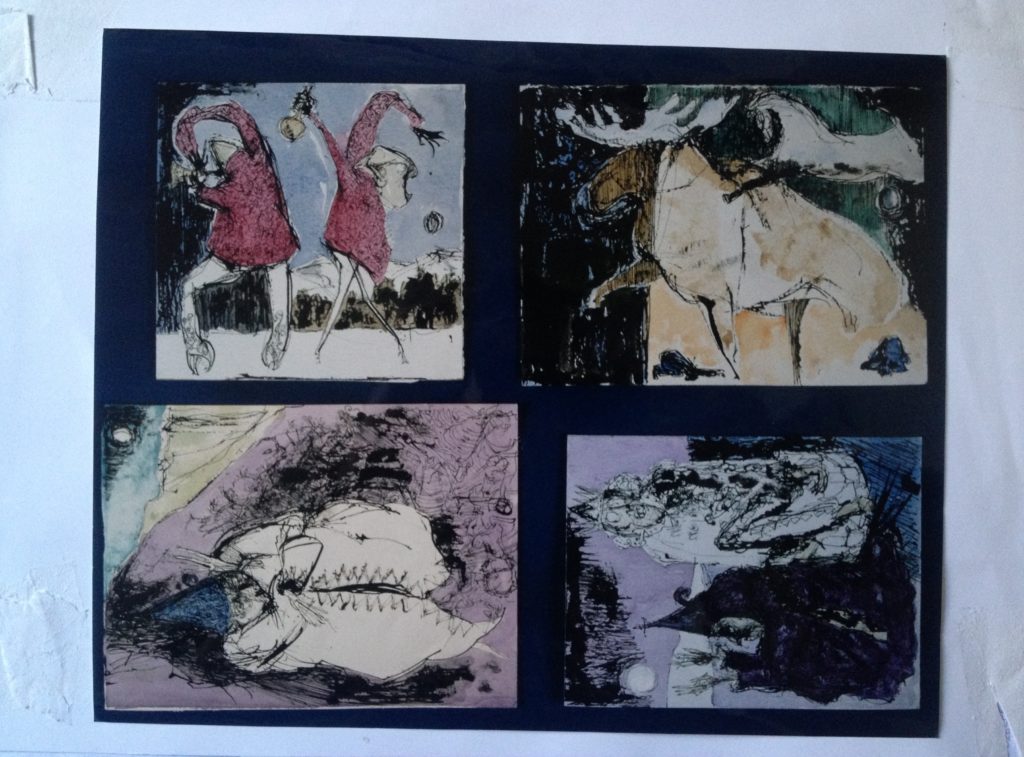

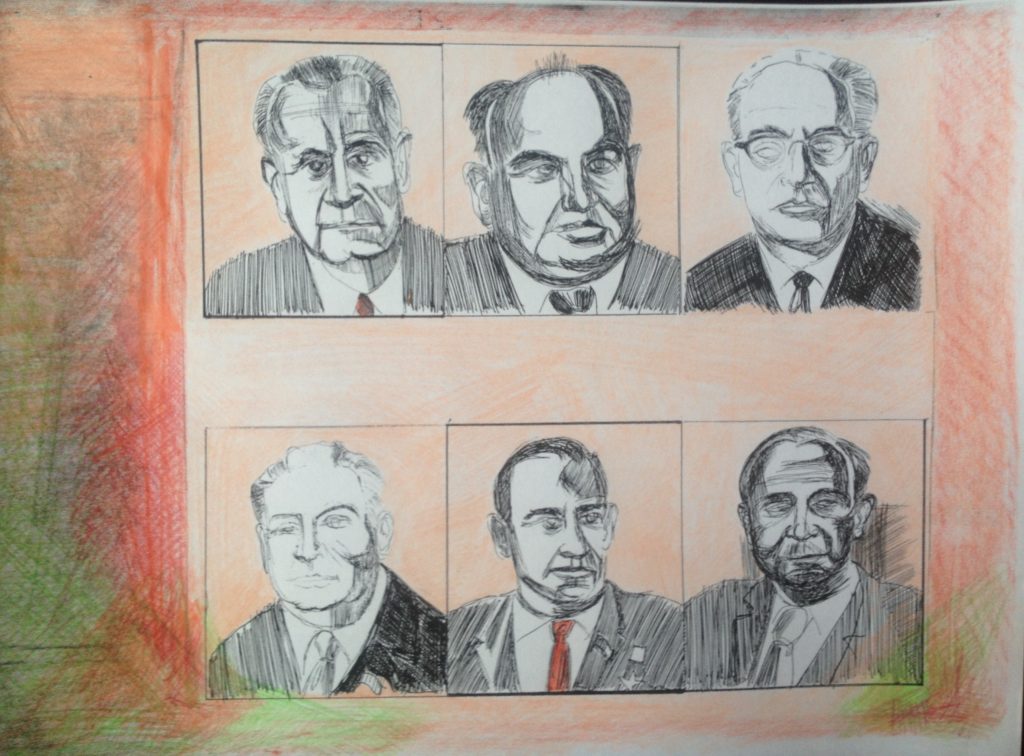

Memories can be cut out and rearranged. But that doesn’t make them better or any easier to grasp. Looking at these three new additions to the museum, the curator can’t help but wonder what binds them outside of his own random attempts at fusing or displaying memory. Maybe not even that. Maybe they should be pondered in silence, without recourse to thought.

Blue #3

There is a peculiar shade of blue that pervades certain parts of Accrington. Not always seen, it can nevertheless be sensed as a strong visual memory over long periods of time and sometimes in other places, far removed from this former manufacturing town in East Lancashire. The blue can be put to various uses. In modern parlance, it is a “positive” force. And the curator invoked it at various times during that strangest of decades, the 1990s.

Blue #2

Sometimes you can see a peculiar kind of blue in Accrington. You can normally see it when the sun goes down behind the hill where the former NORI brickworks use to be. (It’s now a new housing estate.) The afterglow spreads over Accrington Stanley’s ground, and then casts a peculiar blue green light into the back room of my parents’ house.

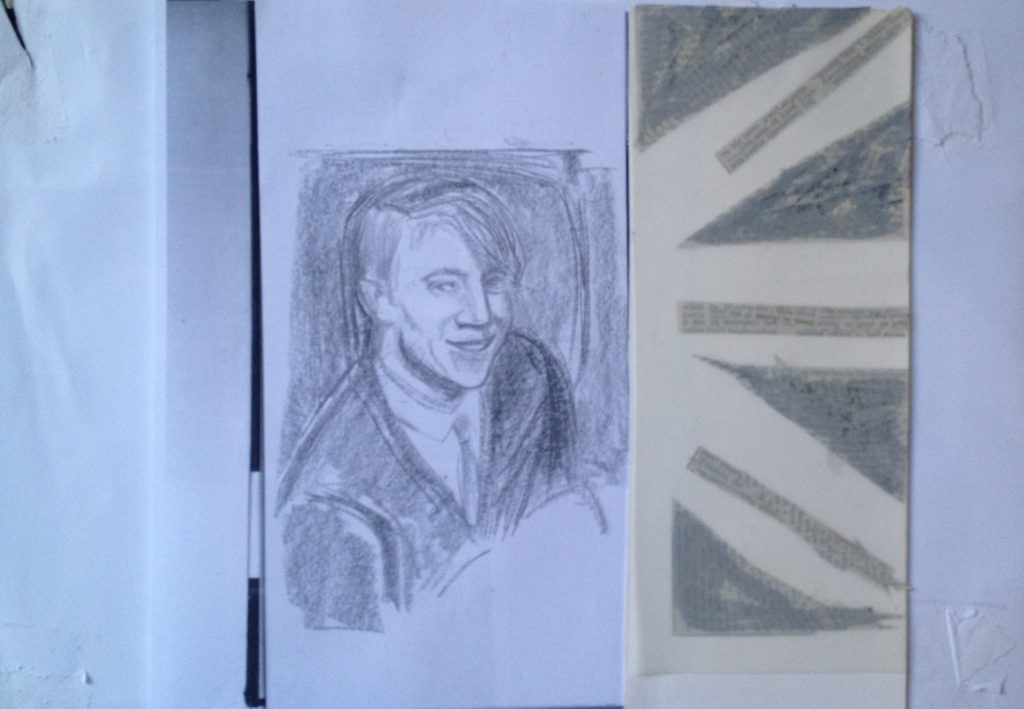

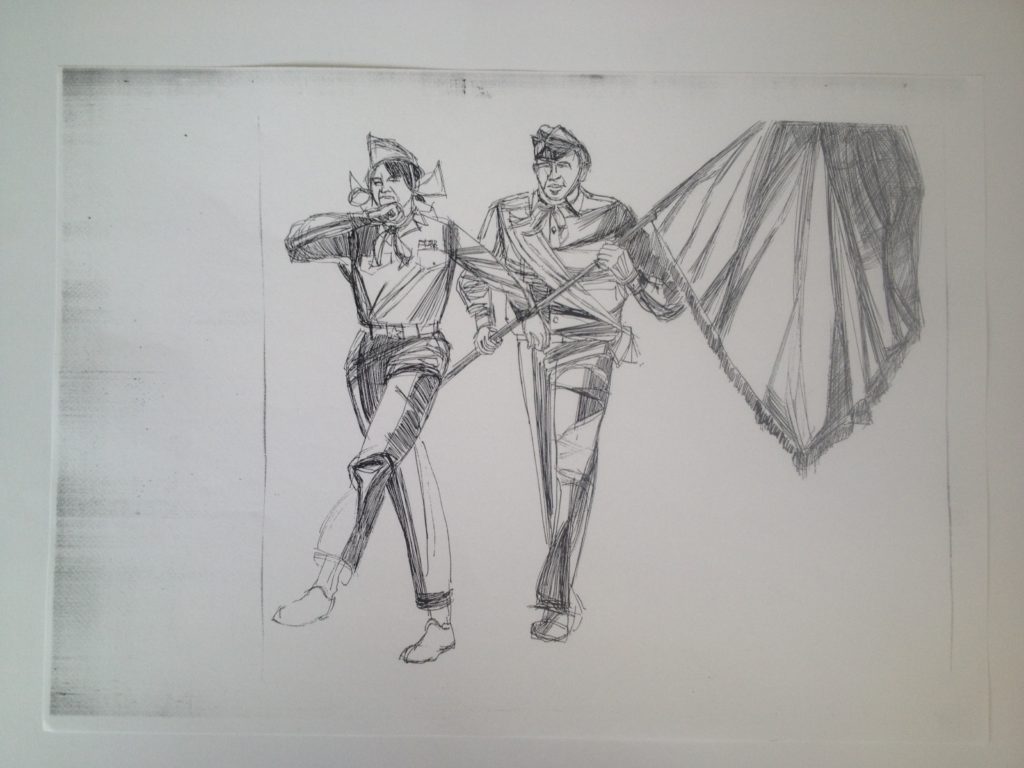

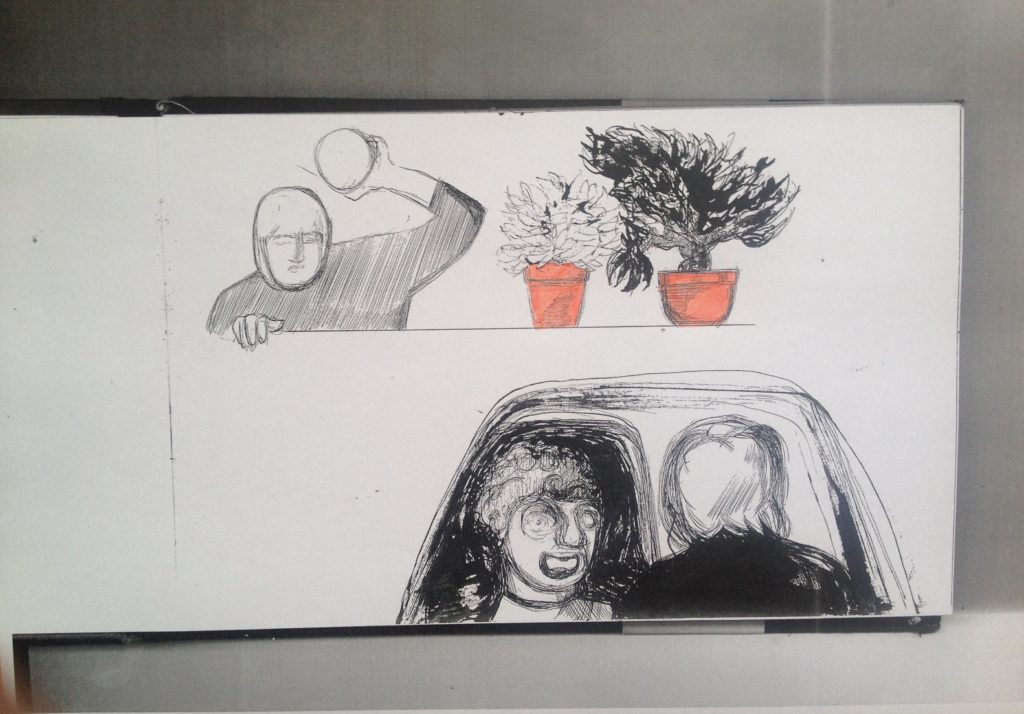

In the very early 1990s, on the dole and living back at my parents’ in Accrington, I began to draw and write in earnest, and in secret. I thought of applying to St Martins’, but couldn’t be arsed. The post ERM crash suited me. No jobs worth having in East Lancashire. Still: I needed a counterpoint to my friends’ exciting lives in dreamlike places like Bedford, Lutterworth or Chalfont St Peter. And, around 1993, London, where my more urbane mates ended up. I started to draw what it would be like to, you know, go there.

Then I would go to the corner shop and buy 4 cans of Trent Mild, and mixed salt and vinegar peanuts and salted crisps, and read the Acccrington Observer letters page and listen to BBC Radio 4.

The past is my playground.

Blue #1

Sometimes you can see a peculiar kind of blue in Accrington. You can normally see it when the sun goes down behind the hill where the former NORI brickworks use to be. (It’s now a new housing estate.) The afterglow spreads over Accrington Stanley’s ground, and then casts a peculiar blue green light into the back room of my parents’ house.

I still find it a remarkable light, something I haven’t seen anywhere else. I always found its appearance a very hopeful sign and – like the two Haitian angel/devil tin cats hanging on my wall – still draw on its presence.

In the very early 1990s, when I left Felling, I spent some time living back at my parents. Sometimes letters from friends, (whose lives seemed to be far more exciting, or at least much more dramatically, entertainingly, boring than mine) would summon up this blue light. Places like Bedford, Lutterworth or Chesterfield, Aberystwyth or Chalfont St Peter loomed large in the imagination. And, around 1993, London. A place seen only three times previously. And then in passing. I began to draw what London would be like, if I ever went.

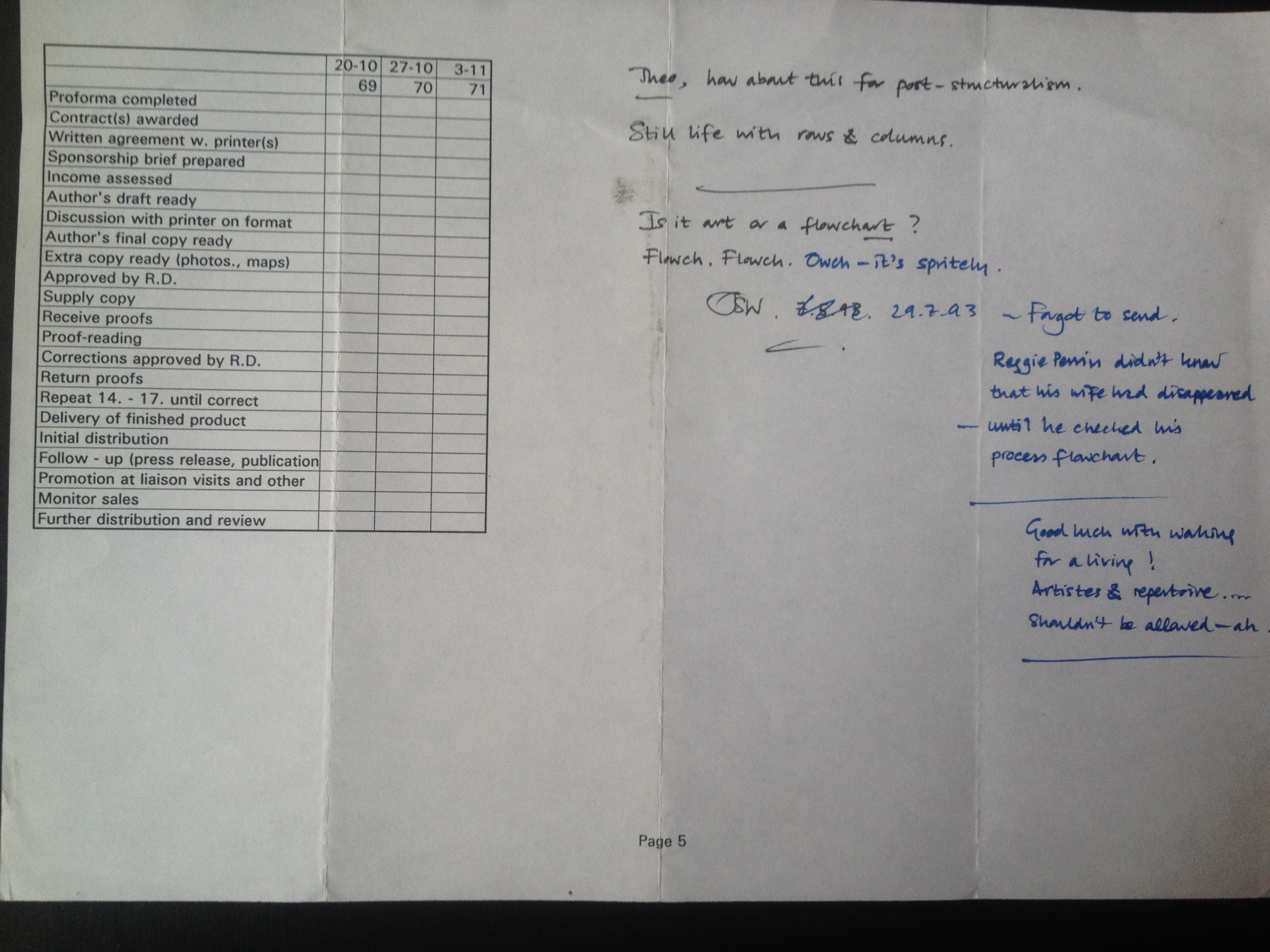

The 1990s, where letters would stop and start amidships, beached by thoughts or sudden displays of emotion. A time when the World of Word Processor leaned like a sinister uncle over your shoulder.

The past is my playground.

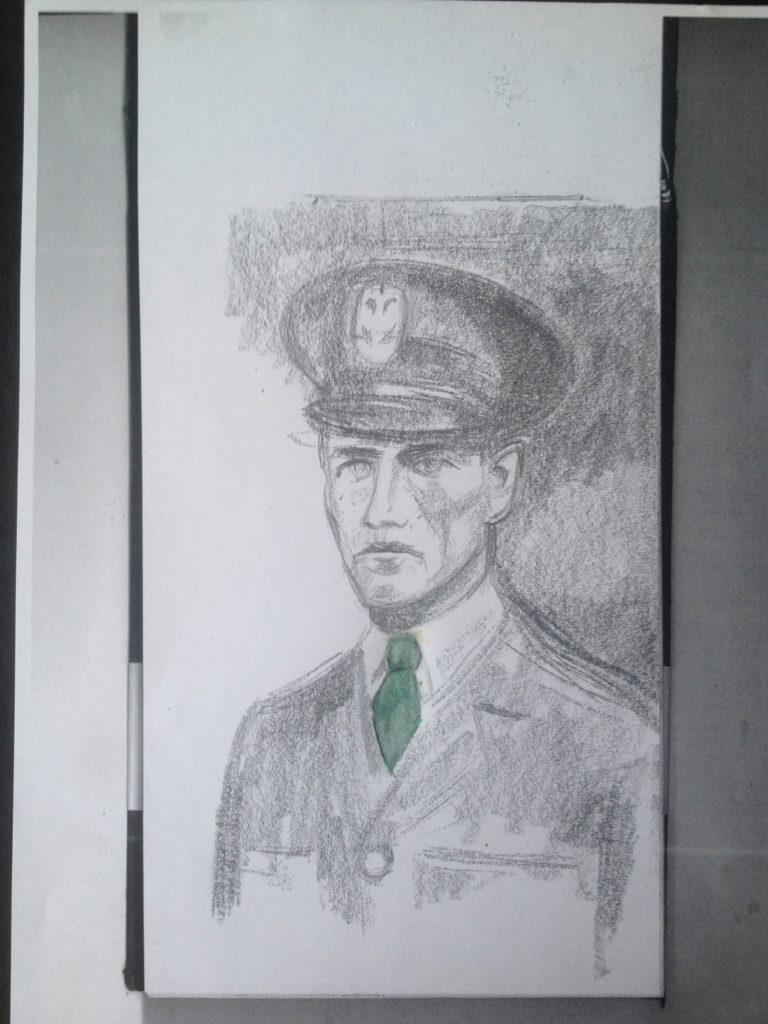

I Never Tell Anybody Anything #4

A reminder that life can be flippant. O, cleanse my flippant soul. By the powers that be, o, stop me from thinking everything can be a joke.

I Never Tell Anyone Anything #2

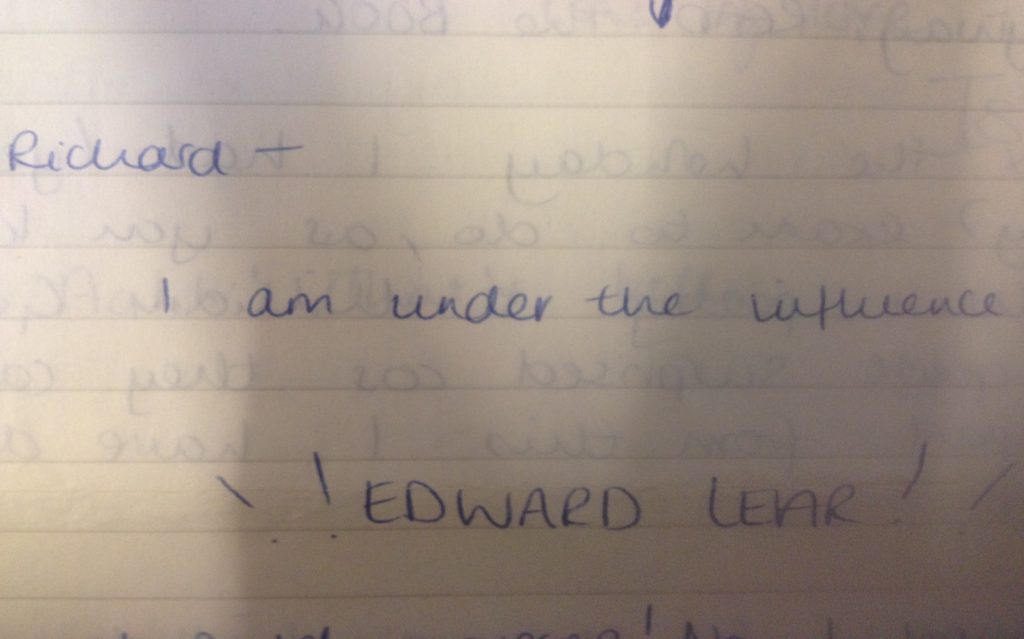

A mini-series of posts dedicated to our Patron Saint, (somewhat slipped), Eddie B. Why should we tell each other anything anyway? Our emotions are being turned into clean code. Very soon we will be shared to death.

I Never Tell Anyone Anything #1

A mini-series of posts dedicated to our Patron Saint, (somewhat slipped), Eddie B. Why should we tell each other anything anyway?

Accrington Red Brick Coalbunker Interzone

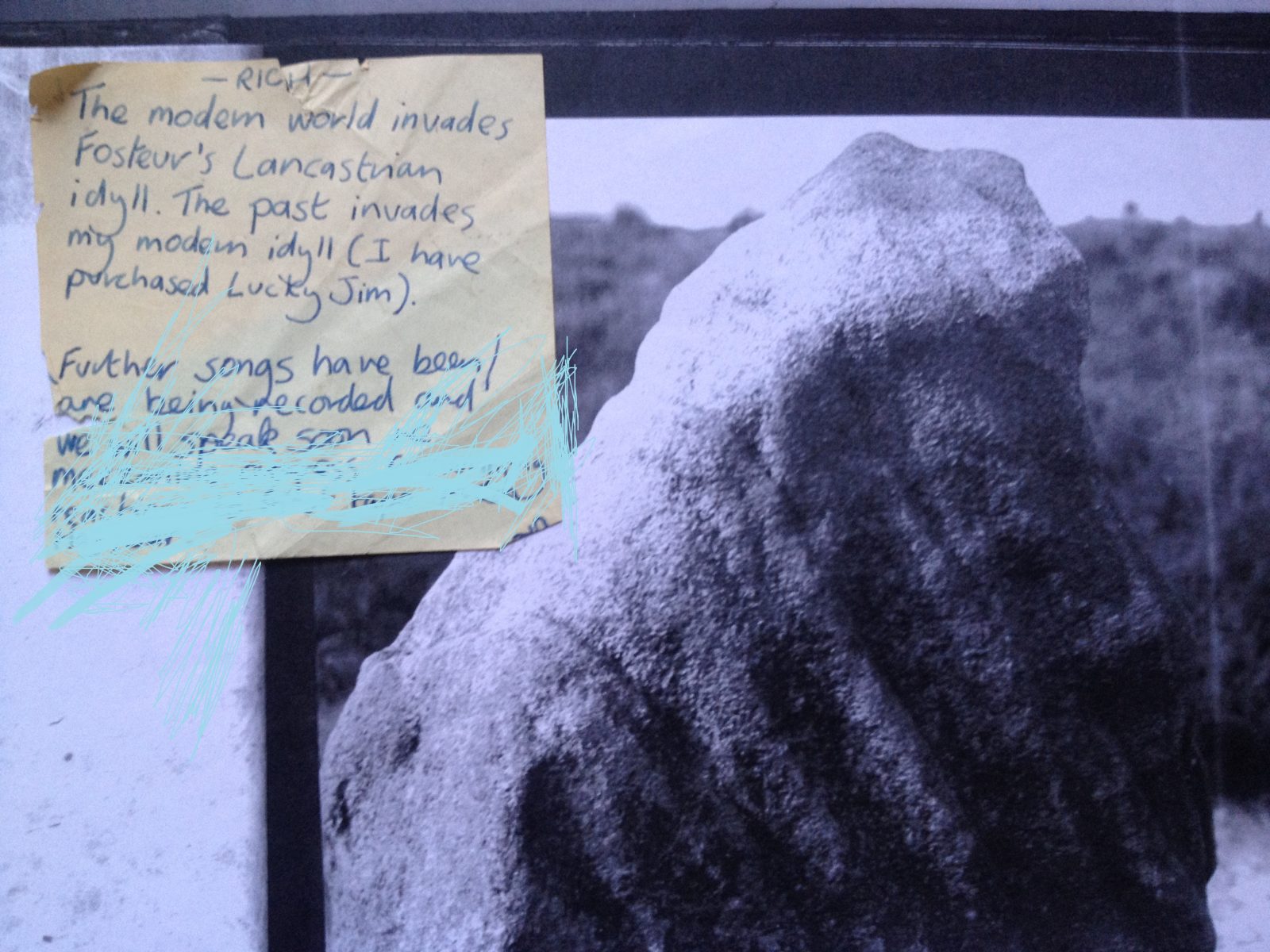

Coal, brick (whether sooty or bright red), clay, soil, stone. These are my elements. I adore the smell of coal cinders. Like the dun green colour of the painted prefabs and shelters then still to be seen at the top of Moss Hall Road, the dank, tangy smell of cinders constitutes a very early memory.

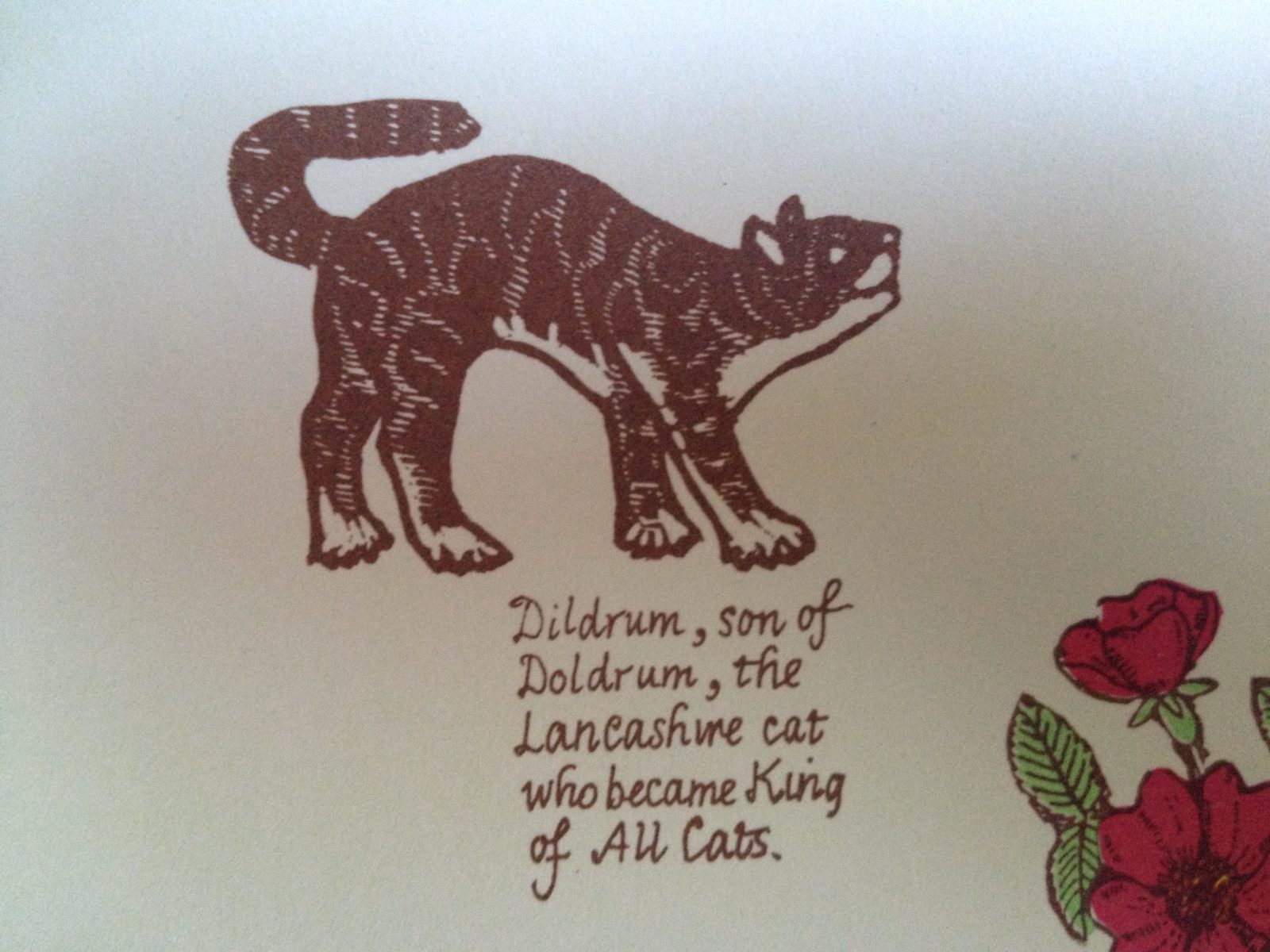

Every week the coal man (a jolly, noisy chap I recall) would drop off a few bags in our concrete coal bunker in our new house on Whalley Road. I would then clamber onto the structure, and try to look into next door’s garden, for their cat Milly (was it Milly?), an irascible tortoiseshell. Or peer over the road to the NORI brick stacks. I would bang my drum (a 2nd, or 3rd birthday present) and wear my dad’s Heworth Colliery Band hat.

My past is my playground.